Namila, the tables have turned so to speak and you’re now in the subject seat. I want to start by asking how you came to be a journalist and broadcaster?

Thank you Rosy! It was actually through community radio. My father worked at the ABC for 49 years, so being in a radio space was where I always felt the most comfortable. Growing up as part of a migrant community, I knew from going on holidays back to Papua New Guinea, how important radio was; it was like a lifeline to my grandparents in the village that connected them to the rest of the world. I found it extraordinary that my grandfather, who had never been formally educated, would sit in the village listening to the BBC, ABC, and Radio Australia and was then able to step into political conversations with my father with a lot of depth and knowledge. I started at 3CR in 1993. Radio as a medium was a much easier way for me to embed myself within Australian media because I felt like the physicality of how I looked didn’t always make it accessible to get into particular spaces. It’s no coincidence that I am at the age I am now, and finally, feel comfortable stepping into television.

You are now the host of the ABC’s Art Works, a show that tackles complex conversations about race, culture and identity through a creative lens. What power do you think the arts holds?

The arts hold extraordinary power. I am moved by the innovation of what artists choose to share. There is a lot of labour that goes into being able to convey ideas or create conversations around really big complex stuff. Artists do it so well and so powerfully, in a way that is not possible, or at least easily done through the platform afforded to a politician, or a bureaucrat, or a policymaker. There is something so engaging when someone is willing to reveal what they prioritise or experience and take that message out to the masses. It sounds a bit twee to say it, but the power of art and artists to invite and engage with the masses to me is incredible.

How do you think the language that we use to describe and talk about artists, specifically those from minority groups, has shaped – for better or for worse – the dominant reception of artists and their art?

There are so many global shifts that are happening, and I think artists are really at the forefront, be it through the world of literature, visual art, or theatre. We are all a work in progress. My ongoing learning and how it shapes the way I see the world makes me mindful that not only knowing better but doing better is very intimately tied in with my use of language. Even with Art Works, we are mindful of ensuring that language is used effectively. What we wanted to do was clear and reset the table to invite everyone to have a seat; because the arts, even as a part of language, has not always been a safe space or an impartial place. It can be very elitist. People from particular groups are not always welcomed. Often they are spoken about rather than to. The way that the arts reframes language and normalises particular vernacular has been key in terms of how society progresses and constantly gets reshaped within the multiple landscapes.

You have said previously that you can use your position to pass the mic on to those artists who don’t always have a chance to hold it. Why is it important to get the voices of minority groups or peoples heard within mainstream media?

Because they exist. They are part of our communities and there is power in being able to tell your own story. I think for those of us who are in leading positions, when it comes to being able to dominate and occupy particular spaces, that a level of responsibility is on us to recognise that sometimes we don’t always have lived experience, which to me is the most important. Even though I am a woman, I am an older woman, I am a mother, I am a black woman… there are various levels of isms that impact and affect my life. In terms of those isms, there are particular ways of being that I have no idea about. And I need to understand that when I don’t possess the level of skills, knowledge, depth and nuance to be able to lead conversations, it doesn’t have to be a big deal to pass the mic over. There is a lot of misinformation that we need to cut through to get to the core of what’s important. There has been such a narrow approach to the way stories, certainly in this country, have been told and that has a much bigger and deeper effect, it shapes nationhood. It’s the same with the arts – who gets to curate spaces and who gets the final say on what stories are being told and who it’s told to? When I mentor students or run workshops, I always ask three key questions when I am creating or consuming content: who is telling the story, who are they telling the story about, and who are they telling the story to. That speaks so much to the level of authenticity when exposed to particular ideas.

In an interview you did with Melbourne-based South- Sudanese artist Atong Atem, Atem talks to the idea of art being an outlet for processing intense issues of race, culture and identity. Namila, on the back of this, do you think that all art needs to be for all people?

No, I don’t. What I love is the discomfort; sometimes people can feel when they can’t relate to a story. As black folks that is something we constantly do – we are constantly adapting and remoulding ourselves to engage with a story. When someone is a part of a dominant power structure, they get used to the ease with which stories are framed and presented to suit their specific sensibilities and the world is not like that anymore. People have to put in some labour, you have to consider things a bit more deeply, you need to think about what your role is within that structure. With stories about power, you need to further disseminate and make room for particular stories to be told. People can take issue with the fact that race and gender is a thing. It’s not like we love talking about race – we hate it – we’d love to just talk about anything to do with the human condition that doesn’t need that as a starting point. There is an empathy deficit within the world today, which I find very bizarre.

Art is about perspective, so inherently when one collects art and brings it into their home, they are bringing different viewpoints from the artist into their lives. How might we begin to understand these viewpoints in more meaningful and authentic ways?

Art is so subjective and why we connect to it is deeply personal. I will not acquire art that I cannot speak to with conviction. If someone is going to flag something problematic or ask you a direct question about the work, it is an issue if you are not going to speak to the broader structural institutional issues. Art Works check in constantly to ask whether I am comfortable speaking to or about particular artists. There are artists who I think dominate and are very lauded for adapting and adopting particular aesthetics that are not their own; when they are called upon to speak to it, they refuse to answer. That, to me, is problematic. You need to be responsible, mindful and ethical in assuring – whether financially, creatively, socially, or politically – that you have a clear understanding of how your contribution plays out.

Can you tell me about the art in your life and in your home? What do you hope your art collection might say about you and your identity as a Melbourne-born Tolai woman from Rabaul in Papua New Guinea?

I have a lot of Papua New Guinean (PNG) art. That speaks to me being a very proud Tolai Melanesian woman. It’s also a part of the migrant experience that we seek to stay connected to the homelands that are the formative parts of who we are in our early years. I have a lot of my parents’ objects that I brought here in the mid-70s. I think my art says I am very sentimental and proud of being Papua New Guinean because there was a lot of shame; and there still is sometimes, in the way Australia shapes and frames ideas as to what PNG is. I’ve got a lot of black art. I’m pretty unapologetically blackedy- blackblack- black with my art. I have an Atong Atem work (my favourite photos of hers), but I also want to make sure that from time to time I dust off things mum and dad have brought down [from PNG] including woven bags which we PNG nationals call bilums. I want to make sure that I am constantly breathing new life into them so that they don’t sit dormant, that they’re not just decoration and are being practically used for what they were designed for. I do this by sharing them with my kids.

Who are the artists on your radar?

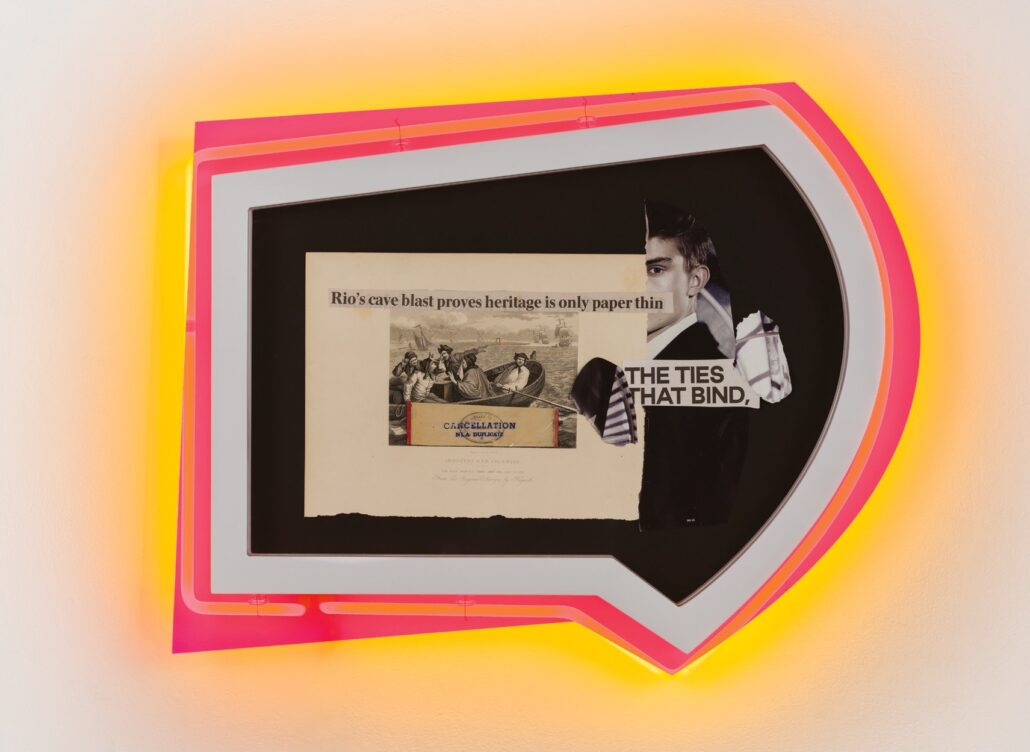

Where do I even start! Zanele Muholi, who I just think is such an amazing South African artist. Their work was the first work I ever saw in terms of imagery, normalising queer black couples in a very intimate photo. I saw these photos about 15 years ago now. They depicted beautiful femmes in the domestic sphere and normalised black love in a way that I had never really seen up until that point. Brook Andrew who is also a dear friend… where to start with him! Eric Bridgeman, a Papua New Guinean artist based in Brisbane who does these enormous and beautiful PNG shields. He goes back to the highlands in PNG and makes with the community. The whole process allows proceeds to go back to his community and his family. Lisa Hilli, another PNG artist, Maryann Talia Pau who is a Brisbane-based Samoan artist, Maree Clarke… I could go on and on!

Featured Image: Namila Benson in her home. Photo: Nick Harrison. Courtesy: Namila Benson.