In the shady recesses of Facebook lives a page named Cursed AI. Its bio reads: “Step into the eerie world of AI-generated cursed art, where machines possess powers to create twisted and terrifying masterpieces.”

There are images with surplus human limbs protruding from places that make no sense. There are warped faces and celebrities in compromising situations. And – my favourite – there’s Jesus executing an impressive aerial manoeuvre over a table (a misinterpretation of prompt text referencing a biblical episode when Jesus flips tables over with his hands).

Though AI-generated art isn’t technically new, a host of programs released or updated over the past few years have made the technology more accessible than ever. How do such programs work? By mining the squillions of images available on the internet, training algorithms to identify patterns and relationships in these images and then – in response to prompt text – reproducing their own.

While current knowledge gaps can lead to some comical results, the images created can also be pretty striking. And since the technology will only improve over time, some commentators have expressed fears that digital artists could soon be usurped by machines.

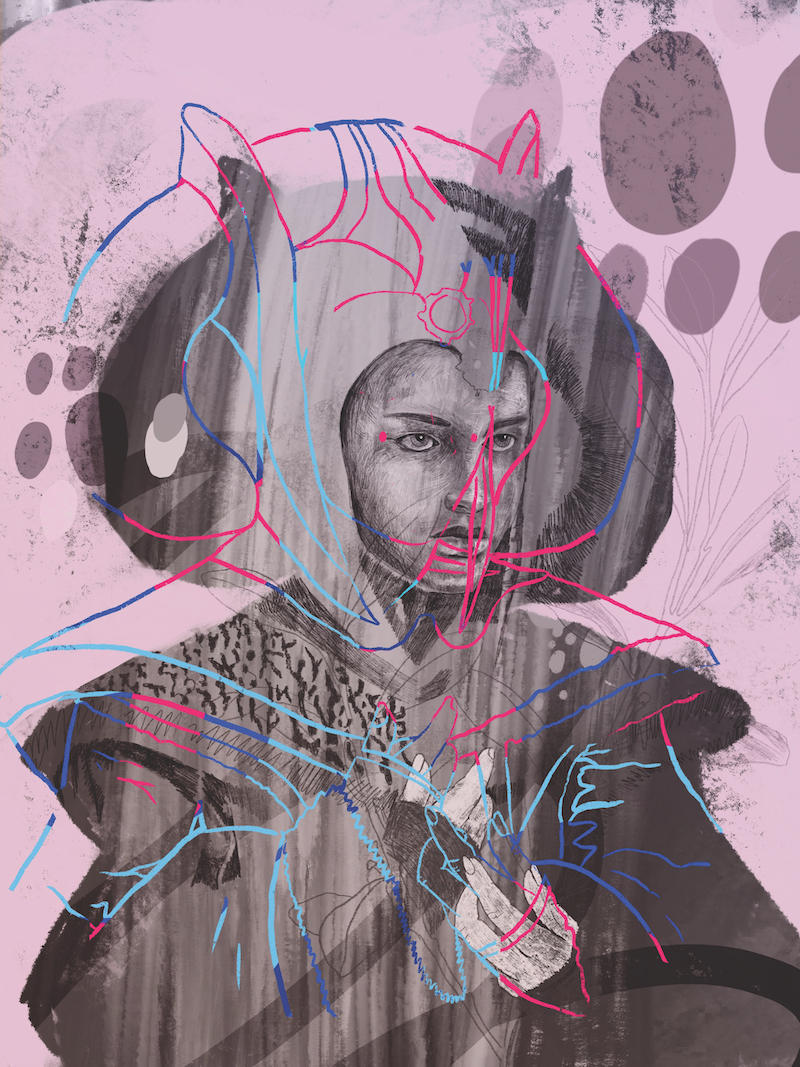

HAPPY DECAY is an Australian digital artist and illustrator with a particular interest in experimental new artistic methods. Using a combination of traditional and digital drawing techniques to produce works ranging from NFTs to large-scale murals, the artist was driven to experiment with generative AI out of curiosity.

“It seems to require a different type of a skill set over traditional and digital art, being very dependent upon prompts and algorithms,” he comments. While HAPPY DECAY can appreciate the way new programs can streamline workflows for certain artists, his own foray into the technology left him disappointed. “My experience was that there was a lot of room for misinterpretation between the feeling of the artist and the image AI creates.”

Others are leaning into the new skill set of ‘prompting’, muddying the waters of what can be understood to constitute ‘art’ and an ‘artist’.In 2022, the Colorado State Fair’s annual art competition awarded first prize in the Digital Arts/Digitally Manipulated Photography category to Jason M. Allen for a work titled Théâtre D’opéra Spatial. The win sparked outrage among other entrants, since Allen – a game designer by trade – had used the AI program Midjourney to create the work.

Allen declined to reveal the text prompt and image set that he spent weeks refining to arrive at the final work. However, the dramatic scene appears to borrow elements from Baroque art. HAPPY DECAY points out that this kind of stylistic mimicry has existed for millennia.

“Within art history, students would study a particular style, learning to reproduce similar marks and gestures to artists within a movement. In some ways, this is how I see AI. However,” he goes on to say, “there is more of an issue when using another artist’s images.”

To date, AI-generated artworks have been known to incorporate the work of living artists, sampling images from the internet without artists’ knowledge or consent. Thankfully, steps are now being taken to ensure that such databases will operate more ethically in future. But this alone may not be enough to ensure fair play.

“Education around the use of AI and its benefits and risks is essential and should become commonplace in schools, universities and businesses,” says Michelle Wang, digital art strategist and curator at Sugar Glider Digital. “Crucially, I think we need to strive for legislation and organisational governance that draws the line as to who the creator of an AI-generated artwork is,” adds the former lawyer.

As for the argument that generative AI spells the obsolescence of human digital artistry, HAPPY DECAY remains optimistic, likening the technology to the introduction of the musical synthesiser.

“When they first came out, some said there was going to be no need for musicians anymore. This didn’t happen. It just added another tool that musicians could use if they so wished.”

The artist concedes that AI may impact some of the processes and opportunities for those creating digital art for commercial purposes – “but not a digital artist who is crafting artwork from their imagination.”

Ultimately, HAPPY DECAY believes the power to use the technology responsibly and fairly lies in the hands of the humans using it.

“After all, it is a tool that we use – not the other way around.”

Above: HAPPY DECAY, Ladi Jedi, 2021. Digital drawing. Courtesy: the artist.