Zoë Croggon discovered collage by way of an instinctive stumble. There was no great bang to herald the discovery of her calling, no spark or grandiose eureka moment – it was simply meant to be. “When I first stumbled into collage,” she says, “my initial work was traditional, in the sense that it was composed of multiple elements, cut and pasted onto a single surface.” But for the 15 years she has dedicated to this practice, Croggon has found that the more she made, the less she used. Now, her art comprises two distinct elements. “I love the simplicity of that gesture,” she confesses, with all the easy assurance of one speaking about an old friend.

Based in Melbourne, she began her art practice proper in her second year at the Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne, whereupon she composed a collage in response to a poem. Since then, she has married photographic unrealities with her background in dance and literature. “I am not a photographer,” she admits, “but I am deeply interested in photography’s ability to produce images that exist outside of representational reality.”

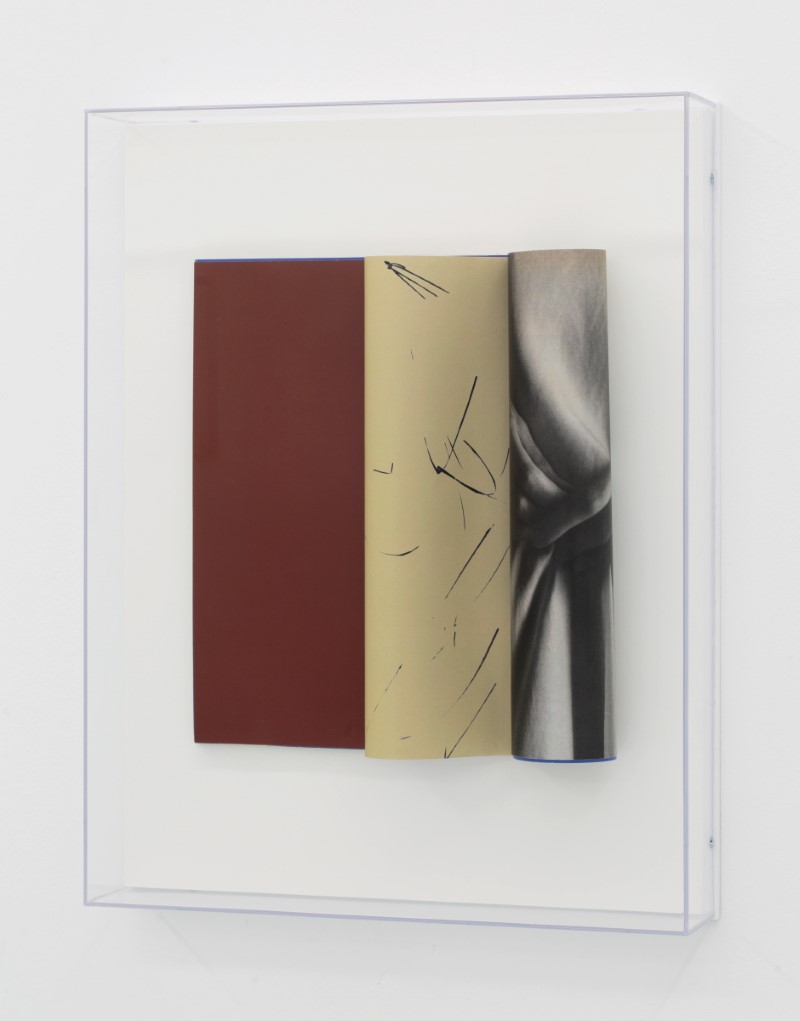

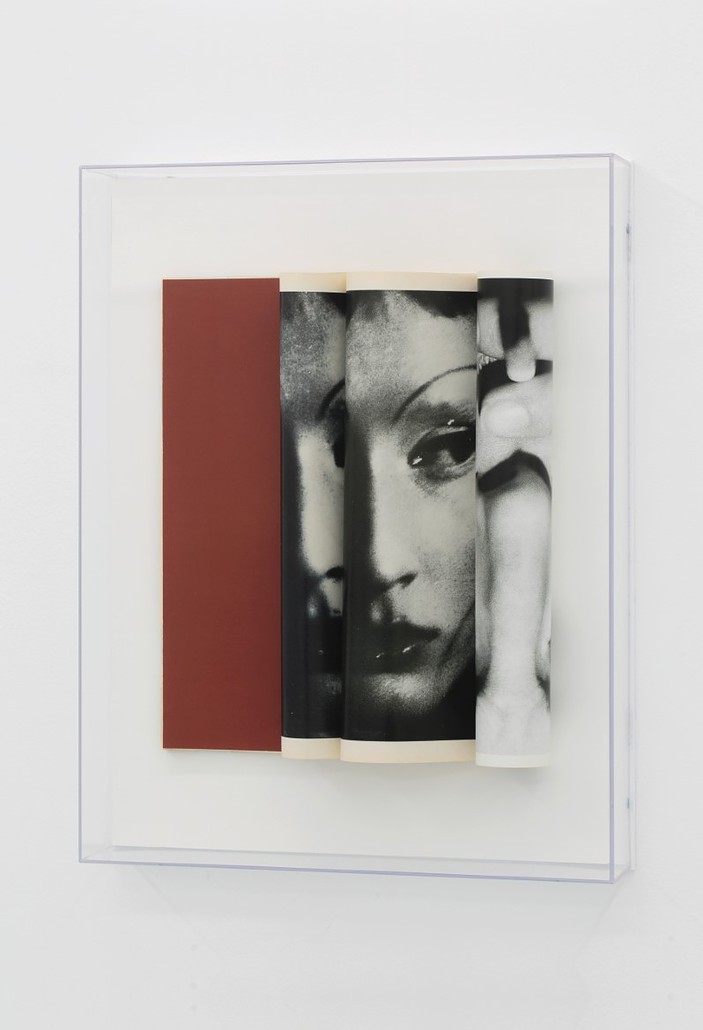

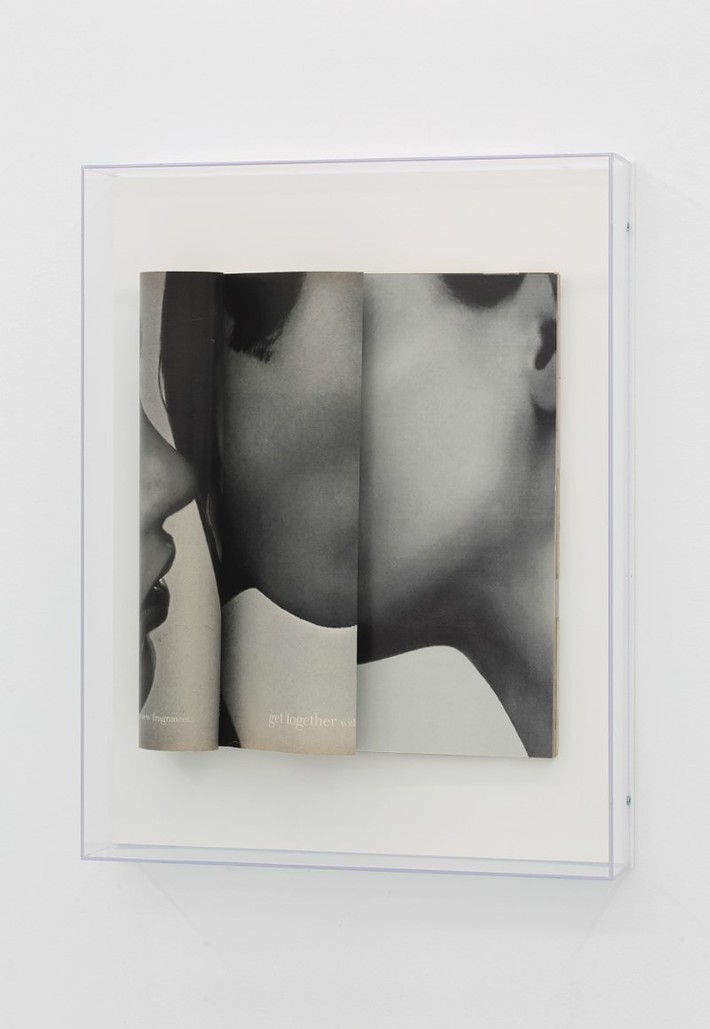

Using found and printed material that has been discarded, donated or abandoned lends her work unique qualities. “Ben day dots, halftone dots, variations of paper, how the ink degrades over time or is bleached by the sun” all confer uniqueness to each work she produces. Most recently, Coggon has focused her practice on magazines as a medium, and these, she says, “require a lot of archival attention because they are not intended as art objects.” The process of preparing them for framing requires reinforcement of their spines, their pages to be supported with harnesses and the folds she adds to be fastened with durable acid-free archival tape. “And all that needs to be invisible!”

One would think that her work might therefore appear unwieldy, but this simply isn’t so. Her art is marked instead by soft delicacy. In Mother Tongue, there is the suggestion of faces reaching closer, cheek extended, lips parted. There is sensuality in the play between imagery that does not quite join at its edges: jaw fails to meet chin and lips never quite touch skin, leaving our minds to conjure images of our own.

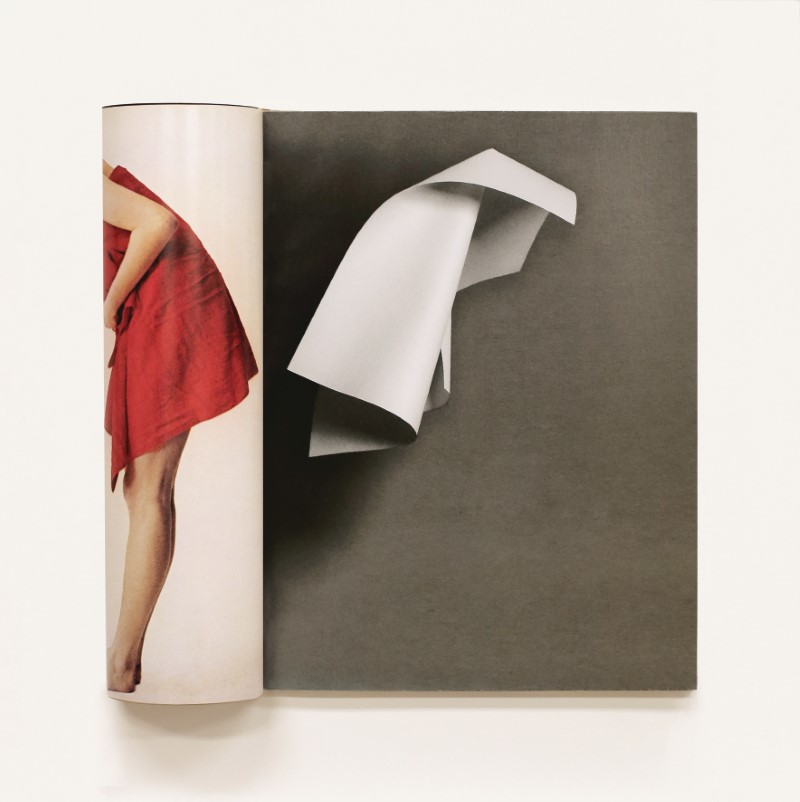

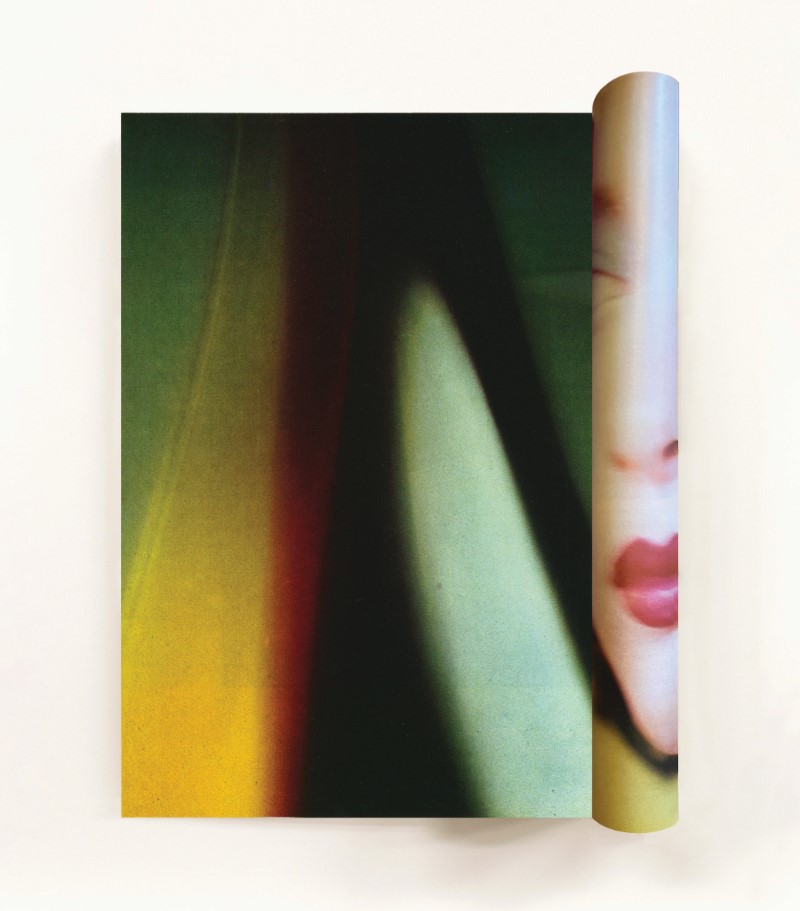

There is the interplay of playful personification in Croggon’s work too that, as in Shadow, leaves plenty of room for us to find our own meaning. Bent is the body of the woman in the red dress. Bent, too, is the folded paper that leans away from her with the same curve as her spine. The veiled half-visage in Seeing Darkly bears similar allusions, leaving us to imagine the gentle folds of green, red and black fabric – or are they multihued rays of coloured light pouring in through stained glass? – as the woman’s hair falling to conceal her face. There is delicacy in these works, a sort of dance that speaks to the poetic beginnings of the artist’s journey into the realm of the humble collage and all the places her practice might still go yet. It is a journey to which she invites us, and one we eagerly follow.

Represented by Daine Singer, Zoë Croggon is presenting a solo exhibition for the Melbourne Art Fair in February 2024 and a public art commission for PHOTO2024 using the performing arts archives of the Arts Centre and The Australian Ballet.

Above: Artist Zoë Croggon. Photo: Martin King. Courtesy: the artist and Daine Singer, Melbourne.