Disruptions, fractures and glitches power Emma Langridge‘s practice, and the paintings, composed with abrupt diversions and skews within rigid line patterns, express a message that nothing in life is perfect. Louise Martin-Chew writes.

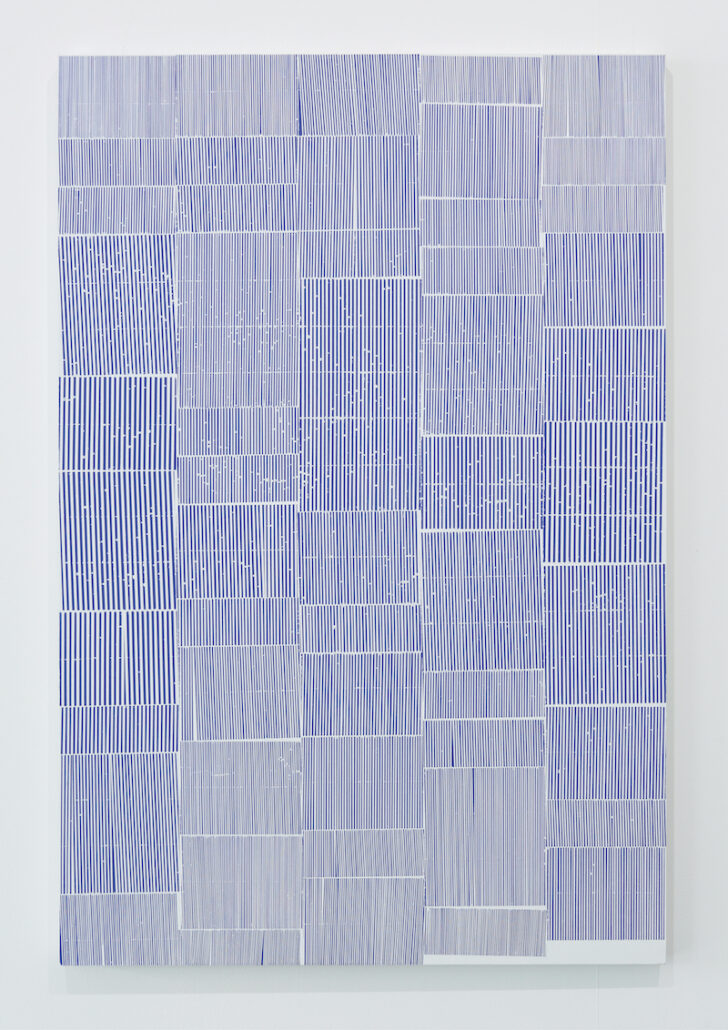

At the heart of Emma Langridge’s abstract painting practice is an investigation of line, explored as a striated surface, constructed with a ruler, tape and paint on a rigid backing. However, it is when the line is disrupted, developing a fracture or a glitch, that these paintings become compelling, both for their viewer and Langridge herself.

Drawing biographical parallels with an artist’s practice may be fraught, but it is possible to see changes in direction arising from personal glitches in her life influencing her intriguing aesthetic.

Langridge was born in the UK and moved to Perth with her family aged 6. Throughout her schooling she planned to become a photographer, but a bout of ill health in her final year of high school saw her, “on my very last day, completely sweep aside my previous plans. I applied for the fine arts degree at University of Western Australia. It was a small class, with only 20 or so students, within an architecture school.”

In Cumber (2021-22), amongst the work to be seen at Sydney Contemporary with Five Walls Gallery, a black surface is incised with red lines, fractured across the plane—diagonally, horizontally and vertically—with discontinuations. They begin below a horizontal band of black at the top with lines wavering away from the vertical. Small irregular areas catch the eye and pause movement. It reminds me of the way narratives are constructed — it is when the unexpected happens that our attention is caught.

“In my final year I was doing the art practice subject when I suddenly started painting the way I paint now. I was in the fine art studio late at night. I realised I didn’t want participate in this huge tradition of painting, but wanted to contribute my own way. I looked around me in the studio and there was MDF and metal rulers, masking tape and model building. I picked up the materials I had right there and started. I thought, ‘I’ll keep doing this until I’m finished with it’. That was 25, almost 30 years ago now. I’m not finished.”

In 2001, she relocated from Perth to Melbourne. Her method and tools have changed little over the years, although her decision to study toward a practice-led doctorate in 2014 created context. Like her initial decision to head to art school, it emerged from another personal glitch.

“About ten years ago I was again very unwell, and my mind was very hazy. I decided I needed training that could support me, and I was thinking about an accounting diploma. A friend said, ‘Life is short. You should apply to do an MFA or a PhD.’ At the time it wasn’t even on my radar. But for some reason it struck a chord. So, instead of signing up for something quite responsible, I applied for a PhD. It seems to be the way of my life!”

Langridge has shown her work all around the world, having been engaged in an international conversation about constructed abstraction since about 2007. The artists she corresponds with “are from places like the Netherlands, New York, France, and Germany in particular, countries with a larger, visually articulate population, of people who grew up with De Stijl and pure abstraction.”

The seven paintings to be shown at Sydney Contemporary build on previous exhibitions and public art Langridge has created in Sydney. Quarter I and II in black and yellow are twin circular works that speak to each other while are also contained in their own orbit. The line splits and ruptures, held in tension with its geometries.

/ If the line is a signal, the break in the line becomes noise. It is this disruption which I investigate through my painting practice. / Emma Langridge

In Langridge’s work she finds a form of machine-mimicry, with a disruptive tactic that reaches toward the analogue. She said, “When the machine encounters a disrupting element, the task continues unabated, forming a glitch.”

Blindspot is painted on a circular base. Strips of tape do not uniformly reach to the edge. Vertical lines are balanced with horizontal bands of white, but nothing is rigidly constructed. Its formality is offset with an organic sensibility that gives its two-tone palette a warmth which speaks to Langridge’s method. “If the line is a signal, the break in the line becomes noise. It is this disruption which I investigate through my painting practice: creating the plane, only to break it apart, the fragments dissipating and coalescing into new and ambiguous forms.”

Her market includes institutions – Edith Cowan University, Artbank, Bankwest, Benalla Art Gallery, Holmes à Court, and international collections. Aaron Martin and Misuzu Ueda, co-directors of Five Walls, observe, “Her private collectors come from all different backgrounds but we have noticed a particular interest from architects and designers, who seem drawn to her meticulous use of lines and fascination with geometry.”

While Langridge’s ideas for paintings begin outside the studio, observing broken surfaces like roads under repair, she said, “For me the real trigger is the process. Without contriving, I let the painting happen. I’ll aim for accuracy and then let it skew because, in the world, nothing is perfect.” These paintings possess an aesthetic that builds cumulatively, appearing different from every angle and every viewing.

Above: Artist Emma Langridge. Photo: Hayden Golder. Photos: Tim Gresham. Courtesy: the artist and Five Walls Gallery.

Emma Langridge, How the Light Gets In, 2023. Acrylic on wooden support, 76 x 50.7cm

Emma Langridge, Blindspot, 2023. Acrylic on wooden support, 60cm diameter.

Emma Langridge, Gravity, 2023. Acrylic on wooden support, 91.5 x 61cm

Emma Langridge, Quarter I & II, 2022. Enamel and acrylic on wood, 25cm diameter.